Dad's story prior to meeting Mum

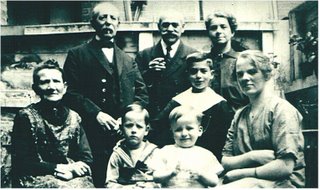

I was born on the 19th of October, 1923 in Arnhem in the Netherlands, the second son of Willem Diederik Gradus LUCAS and Alberta LUCAS ELFFERICH. I was christened Gerhardus Jacobus (I am third from the left in the front row of the photograph above).

My brother, Johannes Benjamin (second from the left at the front), saw light two years earlier, on the 20th of August, 1921.

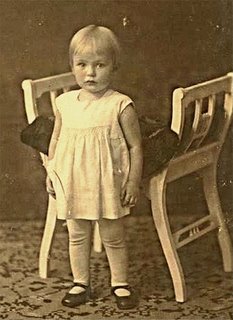

On the 31st of July, 1929, my sister Albarta Grada was born. She was called Bep for short.

My father came from a family of six. He was the second son and child of Johannes Lodevicus Lucas, (1856-1928) and his wife Grada Waltman (1863-1963). She became a centenarian and died in her 101st year.

Opa Lucas, my grandfather, was a painter and sign-writer, as were my dad and his three brothers. They were all very artistic and painted many landscapes and portraits.

Willem, my father, was born on the 18th of December, 1889. He lived through two world wars and the great depression, as did my mother, and he died in September 1964, in his 75th year.

Alberta, his wife, and my mother (extreme right in the front row of the top photograph) was born at Arnhem on the 17th of December, 1894. She died in 1981, in her 87th year.

My earliest recollection in life was when we shifted from Zeist in the province of Utrecht back to Arnhem. Apparently my parents had had some bad luck in Zeist, becoming bankrupt in some business venture. We rented a house at the Geitenkamp, one of Arnhem’s suburbs, and were able to see all of my grandparents on a regular basis again. Opa and Oma Elfferich had bought a house in the St. Antonielaan, number 238.

When my grandmother Opoe died, Opa was quite helpless on his own, and he soon asked my mother, his youngest daughter, to bring her family and live with him. This my parents did. As I recall, this occurred in 1927.

Opa Elfferich lived from 1859 to 1938. His wife lived from 1855 to 1927. Her maiden name was Colenbrander, and she was born in Lochem. Opa was a real character, and, as his name indicates, his forebears came from Germany. He therefore had Pro-German feelings.

He loved Kaiser Wilhelm and the Boer leader, Paul Kruger, and hated the English for what they had done in South Africa. He would never eat oranges, because in those days they came from Spain. Holland had fought an eighty-year war of independence with that country 400 years ago! “I hate that fruit”, he used to say. He had been employed by the Dutch Railways as a head-conductor, and was retired on a decent pension.

My father found it difficult to find regular work. Finally he started a painting business with two of his brothers, but the world was in a depression and so they struggled to make ends meet. We were lucky that Opa lived with us. I am sure that quite often he provided us with eggs, meat and other “luxuries”.

My brother, my sister and I made up our own games and played in the streets with all the other children of the neighborhood. Our youth was carefree. There were hardly any cars or trucks on the roads. I remember standing at the side of the main road from Arnhem to Apeldoorn, counting the passing cars. In an hour we were lucky to count 18 to 20.

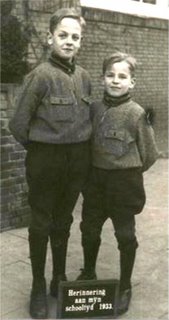

|

| Joop on left, Gerhard on right |

I also want to mention the day that my Uncle Jan, Dad’s older brother, came to visit us one day in 1935, and presented us with a radio he had built. We were the first family in our street to own one, and on weekends our house was full of neighbors listening to the news, especially when a Holland-Belgium football match was being broadcast.

We lived near a very large park called Sonsbeek. It had a deer park, several large ponds, and beech and oak forests. It was very hilly and an ideal playground for children. The winter months were fantastic, and we skated and sledged to our heart's content.

There was an emphasis during my early life on Christianity. My dad was an elder in the Dutch Reformed Church. He was a religious man, born a Roman Catholic. He converted to Protestantism shortly after he got married.

In 1939, the year that I got my Diploma of Secondary Education, things were still tough economically. I was looking for a job and got one as an apprentice photographer with a large industrial firm that tested electrical goods. I worked in the darkroom mostly, and was earning 15 dollars (guilders) a month. It wasn't much, but it beat my brother's 10 dollars.

I started my job on the 1st of September, a few weeks before Hitler's armies invaded Poland, and Britain and France declared war on Germany. However, life went on and really nothing much happened during the first winter of the war. Holland stayed neutral in the conflict, hoping to repeat her neutrality from the First World War.

Then came the month of May, 1940. We had beautiful spring weather. I remember our cousin, Rinus, arriving on the 9th on his brand new bicycle. He'd come all the way from Delft, 120 km to the West. He was several years older than me, and a real showoff. He stayed with us for the night. That was when, in the early morning of the 10th, all hell broke loose. The invasion of Holland had begun.

Over the radio Queen Wilhelmina made a scathing attack on the German Reich and declared a state of war . It was a very emotional day for all of us. The Germans made rapid progress. Arnhem is only 18 km from the border and by midday German troops were marching through our city. Only at Grebbeberg, near Wageningen, were the Dutch army able to resist them.

Germany dropped parachutists on many places. When the the Dutch kept stubbornly resisting, the Luftwaffe bombed Rotterdam, erasing most of the inner city. They gave our government - our Queen and her family had in the meantime managed to flee to England - an ultimatum. They threatened to bomb Amsterdam too the next day. So on the 5th day of the war, the 15th of May, Holland capitulated, and we were occupied by Germany. Belgium and France quickly followed.

After those five fateful days, the country slowly got back to normal. Apart from seeing Germans everywhere, it didn’t affect our lives very much. Of course, we all were supplied with identity cards and ration books, which seemed normal practice in wartime. But now the Nazis had everyone on their books. This included the Jews, and it wasn’t long before they started putting all sorts of restrictions on them. One was that every Jew was to wear a yellow star of David on all of their clothing, so they could be easily recognized in the street.

All this time I continued to work at photography. One day, a colleague of mine at work gave me a photograph of Princess Juliana and her two little daughters, Beatrix and Irene, taken in Canada. She had gone there from London, which was considered too dangerous because of the bombing. The photograph was one many that had been dropped over the country by the RAF.

Everyone was very interested, and asked if they could have a copy. So I started printing them off and felt very patriotic. However, I always made sure to keep the negative on me. Then an school friend of mine asked for one too, and thanked me when I gave him one. Little did I know what this would lead to!

On the 5th of January, 1941, I was at work when the telephone operator rang to say that somebody wanted to see me at the administration building. When I asked her who it was, she wasn't able to say, so I walked the small distance, wondering.

When I entered the room, I saw a stranger who introduced himself as detective so-and-so (I forget his name). He asked me to go to the local police station with him. I knew instantly that I was in trouble. He was a Dutch policeman, and he wouldn't tell me what it was all about. In a police car we drove to the station.

My brain raced, and I thought of the negative in my pocket. I was wearing baggy trousers, 'plus fours' they were called, and I managed to slip the negative from my pocket into the top of my trousers, from where it slid down as far as my calf, where the trousers were tied.

Once inside the police station, I was put in a cell where I had to wait for several hours. During that time, I fished out the negative, then chewed and swallowed it.

Eventually the detective took me into a room. He told me he'd learned that I was distributing photos of members of the Royal House. Would I tell him where I got it? I did not intend to name any names, and told him that I had found the photo in our letterbox. He didn't believe me, but I stuck to my story. In that case, he told me, he had no option other than to hand the matter over to the Gestapo, the German Secret Police.

He took me to the local jail, and I was put into a communal cell that had four prisoners in it already. At night, we were locked in iron trellis cells separated from each other. After about a week, my name was called out, and I was taken to the Gestapo Headquarters where they started to interrogate me.

However, I stuck to my story even though I was hit on the head and forced to do knee bends until I couldn't get up any more. I told them repeatedly that I had no further information for them.

At some stage somebody walked into the room, and lo and behold, it was the old “school friend” to whom I had given a photo of the royals. He had been called in to identify me. He was obviously a German sympathizer.

After some more interrogating, I was taken back to the prison where I was to stay for 8 months. During that time, my parents were allowed to visit me only twice.

Then one morning, I was suddenly taken along to the Gestapo again. On the way there, all sorts of thoughts went through my head. But nothing happened. I was just given a garden fork and ordered to do some weeding. After being cooped up in a cell for so long, it seemed like being in heaven, especially as the weather was summery and warm.

The garden sloped gently, and was huge. I had been working for about an hour when I saw an officer coming towards me. He looked at me quizzically, and then I recognized him as the man who had been present when I was interrogated months ago. He asked me how long my sentence was. I told him that I had not been to court yet. He looked very surprised, and promised he would look into the matter.

At about 17.00 they took me back to prison. The next morning my name was called out again, and I was again taken to the garden where I happily picked up my fork. Anything was better than lingering in a cell. An hour or so passed by, and I felt on top of the world, weeding away in the late August sunshine. Then, the officer from the previous day turned up and told me to come with him.

Inside headquarters, I was again led into another room. The face of Hitler stared at me from a frame on the wall. An officer sat behind the desk. He gave me a lecture about cooperating with the German Army. A piece of paper was shoved under my nose. It stated that I promised I would never again work against the Nazis. Otherwise they would send me to a concentration camp.

After I signed it, the officer shook my hand, and a minute later I found myself standing in the street, a free man.

I paused for a while, thanking my lucky stars, and the officer who had started the ball rolling. I guessed that my file had been put in some drawer and then forgotten. It made me realize that that there are good Germans too.

I never forget the feeling of elation as I walked down the road - the warm sun, the beautiful trees and gardens, the people walking, the traffic and the realization of being free! What an incredible experience. You should have seen my family's faces when, totally unexpected, I walked in!

We had a great party that night, and all the neighbors came in to congratulate me. I got my job back, but found I couldn't stand being cooped up in a darkroom anymore. Therefore, I applied for another job. I was soon accepted as a clerk at a semi-government department, and life returned to normal.

The autumn and winter passed. In late February 1942, sitting down at our evening meal, Dad told us that he and Mum had decided to take in a small Jewish boy for the duration of the war. He came from a family of four, and his parents and little sister would be staying at different addresses. The persecution of the Jews was well on the way, and the church and resistance movement had been looking for suitable hiding places. Dad was a very religious man, and felt it his duty to do his bit.

The boy, Nico Bohemen, arrived a few days later. He was 11 years old, had strong Jewish features, and was very well behaved. We liked him instantly. Our life changed dramatically from then on, because, although Nico wasn't allowed outside, we sometimes took him for short walks on dark nights. He had to stay away from the windows and avoid making too much noise, as we had neighbors living to our left and right, and even above us. But it wasn't long before his little sister came to stay as well. Temporarily, Dad was told, until they found other accommodation for her.

Two weeks later, I was asked to go to an address two kilometres away to fetch the children's mother. She needed to leave her hiding place after being informed that the German Army was going to billet two officers at that address.

I went there in the evening on my bike, loaded her travel bag on the carrier, and we walked all the way home, dodging busy streets and intersections - a very scary trip. However, it all went well. But then, a fortnight later, Dad got a phone call from a shopkeeper in the centre of town, begging him to come and collect Mr. Bohemen too. He was very fearful of being discovered by the Gestapo.

Arrangements were made for Dad to meet him at 21.00 hrs, when it was dark, under the viaduct that crossed the main road to Apeldoorn. When he got there at the given time a man lit a cigarette, letting him know that he was the Jew.

By then it was mid-June. Certainly, having to hide four Jews hadn't been my parents' intention, But there was no going back, we all realized, so we were determined to carry the whole operation through.

Food was going to become a problem, as every citizen had by now been supplied with a ration card. Every month a new one had to be collected from a distribution bureau. Of course the Jews were now excluded from getting one, but were promised a new card every month by the resistance. These cards were obtained through raids on the distribution bureaus, of which there were hundreds throughout the country.

Mum had to be very careful buying food, and so she did her shopping in several shops. But the biggest worry was unexpected visits from neighbors and other people. We had to make sure that the Jews were then downstairs in their sleeping quarters.

One day my sister Bep was standing by the window looking out into the street when suddenly my mother‘s sister, Aunt Sina, turned the corner. She was heading toward our place. Aunty saw Bep at the window and waved.

“Oh God, the Jews!” Bep ran to the back of the house to warn them, but by the time they had disappeared our aunty, expecting the front door to be opened immediately, had angrily pushed the bell several times. She was furious when Bep at last opened the door, and lambasted her for letting her wait so long.

Another time that our aunt called, my mother was in the middle of making an enormous pan of pea soup. For that, she needed to think of a reason. We often used to have relatives or friends stay the night, but now we had to come up with excuses. For example, “The children are sick,” or “We're sorry but we won‘t be home then.” The strain grew heavier as time went on, and it caused mum to get the shingles. Somehow we all persevered.

In September of 1942 Dad decided to build a hiding place in the little alcove downstairs. He put up studs over the width of the room. It was dark there, because there were no windows. The only light it got was from the front room. Dad put scrim over it and wallpapered the entire room. He fabricated a trapdoor that opened from the bottom, so as to let in the Jews behind the surrogate wall. They would then pull it shut from the inside. It was an ingenious job, and gave everyone much more confidence.

The hunting down of Jews had begun in earnest, especially in Amsterdam where there was a big Jewish population. Meantime, during the cold winter of 1943, it became clear that the Germans were getting into difficulties in Russia. More men in Germany were called up, and so more slave labour was required. That was the time when young Dutch men began to be forced to go and work in the factories of Germany. I too was called up by the Labour Department. I was to report at a certain date, early in the morning, at the railway station.

We called a family meeting. We needed to decide what to do. Should I report as demanded, or go underground? I decided I'd better go, because I didn't want to put the family at risk. It was agreed, and good old Dad made me a suitcase of plywood.

When the day arrived for me to leave, I said my good byes. I had to walk, carrying my heavy suitcase to the railway station, where I saw roughly 100 young men, all packed and anxious. We had been promised that our identity papers would be returned to us before boarding the train (they had been taken off us when we reported at the office a few weeks earlier) but now we were told that they would be sent on later.

I realized that we would just be slave labour in enemy territory. We would be without any proof of identity, somewhere in the middle of Germany. At that moment I planned to escape as soon as an opportunity presented itself. We were put into rows, and one of the guards, a Dutchman in a black uniform, counted us. There were about ten guards, who travelled with us in the train.

During the trip, I managed to change some Dutch money into German currency. I thought that it might come handy later on. We travelled into the Ruhr region, and after two to three hours, the train stopped. We were at Dortmund, and were ordered to get off and form a column. Then we started marching. As we left the station, we realized that most of the buildings lay in ruins. Dortmund had been bombed by one thousand RAF planes a few days ago.

We were marched through hastily cleared roads, where many of the ruins were still smoldering. I was trying to think of a way to escape. I kept to the rear. I pretended that I could hardly keep up. The guard turned around now and then to urge me on. Then, as we came to a corner, and the next-to-last man disappeared around it, I took my chance. I turned on my heels and started running back the same way we'd come. I dreaded to hear a gunshot, but there wasn't. It is amazing how fast you can run if your life is on the line!

Nothing dreadful happened, and after an hour or so I arrived back at the station. There, I joined a line of people waiting to be served at the ticket counter. I listened to the way that they asked for a train ticket. I thanked myself for changing money in the train. When it was my turn I asked for a single to Emmerich, a little town near the Dutch border. Then I passed the control point and was on my way. So far so good!

On the train I happened to meet three young men from Arnhem who were going home on leave. I learned that they worked in Cologne. They all had passports, and expected no trouble. I, on the other hand, had no papers at all. We arrived at Emmerich in the late afternoon, and found a small hotel where we spent the night.

Early the next morning, after a surprisingly good breakfast, we walked to the railway station. They continued their journey and left me there, all alone, wondering what to do next. On an impulse, I walked to the river Rhine and saw a large steam-ferry ready to cross the mighty river. I was just in time to board. About midway on the crossing I saw a Gestapo soldier coming towards me, his gun pointed at my chest. “Ausweis!” (identity papers) he snarled.

I honestly thought my end had come. My brain raced for a suitable, credible answer. I knew my freedom and life depended on it!

I told him almost exactly what had happened. Almost.

I had been on a transport, got sick at the border crossing, and had been allowed to leave the train and go to the toilet. I had been violently sick, and by the time that I returned the train had left. I told him that I had panicked. I hadn't gone to the police as I had no identity papers with me. I said that my mother was very ill, and that I wanted to try and get a job near the border. That would enable me to see my mum on my days off. I'd heard that there were jobs to be had near Kleve, and that was the reason I was on this ferry.

He looked at me for several moments as if to ascertain how much or little to believe of my tale. Thinking back, this moment was one of the crises of my life. I guess the way that I looked (very young for my age) and the convincing manner in which I had told my story, persuaded him say to let me go to Kleve. But, he told me, in case I didn't find employment I should come back to the ferry, where he was on duty 24 hours a day, and he personally would make sure I join the next transport. I thanked him from the bottom of my heart. Inwardly I gloated at the way I had fooled him.

Soon the ferry berthed and I walked off the boat, still a free man, and another step further. Walking through the busy town, I couldn't see any damage anywhere. When I arrived at the Labour office I went in and asked the receptionist to see the boss.

She showed me to the waiting room, and soon a thickset official led me into his office. He offered me a chair and set himself down behind an enormous desk. Behind him, on the wall was the omnipresent face of Herr Adolf Hitler.

I told him - the man, not Hitler - roughly the same story. I emphasized that my mother was very sick. I had to be able to see her on a regular basis. The man looked sympathetic. He seemed to like me. He used his telephone to talk to several people. When he put the phone down he told me that there was a job available at a timber mill near the border. Was I interested?

Was I ever!

The man then asked to see my identity papers. When I told him that they were still in Arnhem, he got angry. But not at me - at those stupid Cheese-heads (how the Germans referred to the Dutch). He issued me a note with several important-looking swastika stamps. He told me this would take me right to Arnhem. I was to go to the labour office there and show those Dummkopfen his note.

Feeling light as a feather, I left his office. I went to the railway station, bought a ticket to Arnhem, and rang our front doorbell only a few hours later. Everyone at home was amazed at what I'd done, and I wonder about it as well, even as I'm writing this.

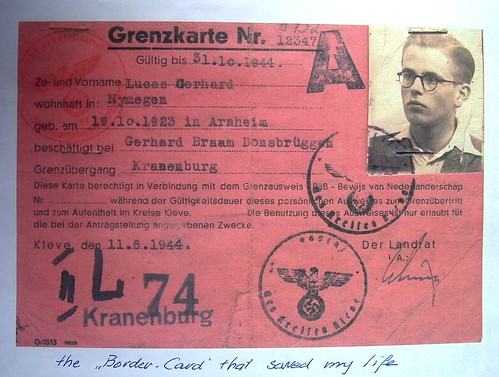

The next day, after showing the German‘s note, the people at the labour department couldn't give me my papers quick enough. Consequently, the next morning I went back to Kleve. I saw my savior again, and this time he presented me with a stamped Grenzkarte (a border-crossing card). He even took me in his car to my place of employment in Donsbruggen, a small village just across the border from Nijmegen in Holland. I still have this Grenzkarte, and I can tell you that it has saved my life several times over.

Well, the job itself was tedious, and not worth my telling you about. At 05.00 in the morning I had to leave home to be at work on time at 08.00. I would returning in the late evening at 09.00.

After a few weeks at that job, I got a weekend off. It was springtime, and the cherries were ripe, so my brother and I and a couple of friends got on our bikes and pedaled to the Betuwe orchards. We had a glorious time eating as many cherries as we could. We also took back several kilograms for the folks at home.

The next morning, I was on my way back to work. At the border we had to get off the train and go through customs to show our grenzkarte. Suddenly got a horrible cramp in my stomach. The customs officer saw me grimace and told me to go to the toilet. There I was violently sick. When I came out, he told me that I still looked terrible, and that I should go home to see my doctor.

I agreed heartily, but by the time I was on my way back to Arnhem the cramp had already subsided. I was well aware what had caused it. But I was cunning. I saw a chance for me to get a day off work. I did go and see my G.P. and when I told him the story he grinned at me wickedly and gave me six weeks sick leave.

What he wrote in the letter to my employer I'm not sure. Possibly he said that I had some serious disease or illness. Good old doctor. It was great having those six weeks off. I helped Dad a bit with his work, wondering what I should do next. I made up my mind not to go back. With a good friend, a student, I decided to go on the run into the countryside.

We biked for miles, and ended up on a farm near Raalte, in Overijssel. We worked on a farm for about seven weeks, after which we biked home again to see how things were getting on.

It was apparent to me that the strain at home was terrible. Dad told me that Mr. Bohemen told him that he couldn't stand it any longer, and that he was going to give himself up. My father stood in front of the door and told him that by doing so he would not only jeopardize his, but also our family's lives. The Jewish father then quietened down, and life returned almost to normal.

Then came the big railway strike. Employees of the Dutch railways refused to transport Jews to Germany. Hundreds of workers went underground, and transport came virtually to a standstill. That was in June of 1944, when the invasion of Europe by the Allies started.

One day, I took a walk in Sonsbeek Park with a friend. When we came out at the main-entrance to cross the Apeldoornse road, a German soldier with his gun at the ready came towards us. He demanded our Ausweis.

My friend had his student-card,was allowed to go. I showed the soldier my Grenzkarte. It had actually expired a year ago on 11-6-1943. However, I had rubbed out the 3 and very carefully replaced it with a 4. It was quite noticeable to me that it was a forgery, but for anyone else it might pass as genuine.

The soldier studied it for a while. He asked me why I wasn't at my work. I explained that the trains hadn't been running that morning. We had been told to go home and wait for word from the authorities.

He accepted my excuse and let me go on my way. If he had noticed the falsification, it would have been the end of me, I'm sure. We were two very lucky young men!

When we arrived at our place, I rang the bell, and who do you think opened the door? It was Mrs. Bohemen, the Jewish lady!

I didn't say anything to my friend. He noticed her of course, and looked a bit uneasy. I told him later that she was our cleaning lady, and he never mentioned the incident again. Only after the war did he reveal that he knew instantly that she was a Jewess. He was the only person to ever know that we sheltered Jews.

Then came the 17th of September, the day of the Allied Airborn-troop landing near Arnhem. It all started with a bombardment of Deelen Airport just north of Arnhem. And soon we saw the gliders over the lowlands south of our city, my brother and I hurried to my friend's place from where we could see the whole operation firsthand.

There was an atmosphere of great excitement around us, and in the distance we could soon hear the fighting. It took the Allies three days to secure the bridge over the Rhine, but the Germans hadn't been asleep either. They brought a panzer division in and managed to throw the paratroopers back, inflicting heavy losses. People from the southern part of the city fled northward, and soon every house in our part of the city had refugees.

We took in our Oma Lucas and her daughter and family as well as several others. But when they saw the Jews, the others rapidly left. They were dead scared in case the Nazis discovered them. Only Oma and her family stayed. But we were optimistic and didn't worry anymore about the Nazis. The war would now soon come to an end, we assumed. Wishful thinking on our part.

The paratroopers were thrown back across the Rhine. The operation at Arnhem had failed, and the whole population was ordered to evacuate the city. All 120,000 of us had to go; nobody was allowed to stay behind.

Oma Lucas was 82 years old, and could not walk very far. Dad improvised and made a cart out of two old bicycles, tying planks between them, and by placing pillows and cushions on the planks turned it into something like an easy chair.

The bikes had no tyres; there were none to be had. We all carried what we could, and off we went. The whole population was on the go. All roads leading north, east and west were full of people, bicycles, horse-drawn carriages, wheelbarrows - you name it.

The weather was kind to us though. We had chosen the northern route, to Apeldoorn. Oma was quite comfortable in her makeshift fauteuil, the Jews made themselves inconspicuous amongst us, and my brother and I pulled Oma's cadillac. She seemed happy enough. On we all plodded on, people around us everywhere. It was a real emigration of a whole city - quite remarkable.

We saw German soldiers on trucks travelling towards Arnhen as we turned away from our hometown. We walked for over six hours before reaching Beekbergen, a village 2 km from Apeldoorn. Farmers with horse-drawn carriages were waiting to pick up the weak and sick. Seeing Oma in her makeshift cart, one of the farmers offered us a carriage. He thereby became our 'landlord' for the meantime. It took us half an hour more to reach his farm.

We got out and were shown to the 'deel', the very large shed, built onto the house, that protects all the cattle in winter. On each side the farmer had a spread thick layer of straw. This was to be the communal bed for the 35 evacuees he had taken in. We were all fed thick pea soup and told by the farmer's wife that we could use the big kitchen normally used by the farm workers. It was still late summer so the cows would remain in their meadows until the first frosts arrived in late November.

In a sense it was cosy with so many people lying next to each other on the straw. Many times there was laughter. We had been there for three weeks when the farmer called us all together and told us that there was no longer enough food for 35 people plus his family. He asked for volunteers who were willing to go and look for other quarters. He would supply a horse and cart and take them further afield.

The Lucas family held a family conference. We decided to volunteer, as we were still very scared that the Jews might easily be picked up. And in that case it would become dangerous for us as well. So along with a few others we made up a party of twelve.

The next morning, a horse and wagon were brought in, and by nine the farmer and his volunteers were on the road west to a place in the Province of Utrecht called Hoogland.

The sun shone brilliantly. It felt as if we were going on a holiday. My mother enjoyed it immensely too, and waved to passers-by the way our Queen used to do. But it was a long drawn-out trip and we were thankful to ultimately arrive at a school in Den Ham.

There the headmaster welcomed us and we were let into some classrooms that had thick straw on the floors. The stoves were burning. By the time we had installed ourselves, it was 10 p.m. and everyone was soon fast asleep.

The next day we were collected by farmers from round about. Our family ended up on a modern farm at the Coelhorst which a Castle that had several farms run by tenant-farmers . There were already a number of people in hiding there - five I believe - so when we joined them it brought the total to ten. There was also the farmer’s family of four.

Our communal bedroom was a little room above the horse-stable. The warmth from the horses kept the room comfortably warm. We slept well on straw again. There was plenty of food on the farm, and we never went hungry once during that last winter of the war, called the 'hunger-winter' in the big cities of the Western provinces. There, people were reduced to eating tulip bulbs and all but starved. Many did die from the cold and hunger.

We became very friendly with the van de Broeks, the headmaster’s family. We walked regularly to Den Ham. It took roughly 30 minutes.

The last big German offensive in the Belgian Ardennes failed. We waited now was for the Allies. They began their advance into Germany and Holland. In March, the Canadians liberated Den Ham, and we expected them to turn up at our farm at any moment.

However, for some reason or other they stopped their offensive. This gave the Germans time to put landmines all around the area, and we ended up with a whole platoon of SS soldiers staying on the farm.

People from Amersfoort used to come on their bicycles to the farms to buy milk or potatoes. Often they bartered their precious possessions for food. They didn't know about the mines, and several times we would hear a loud explosion that told us another person had struck a landmine, probably loosing a foot or leg.

The son of the farm next to us went out one morning to milk the cows. He had just entered the paddock when he stood on a mine, blowing off his foot. He crawled back to the house but struck another mine, ten meters from the kitchen-door. It killed him, but nobody dared to go near him, and he lay there for thirteen days.

This happened about a week before the Germans capitulated. They were ordered to clear the mines they had laid, and only then could we get to the young farmer‘s body. We had tea towels dipped in vinegar strapped round our noses, and used rakes to gather what was left from his body. His parents had seen their son‘s body lying there for over a fortnight, unable to do anything. Such is war.

One day, one of the German soldiers asked us if we'd like to do some fishing. My brother and I went with him to the Eem, the little river that ran behind the dike at our farm. There was a small rowing boat moored there.

The soldier took one of his hand grenades, pulled the pin and threw it in the water. There was a big explosion and lots of fish came floating to the surface, we got in the boat and started collecting the fish.

Suddenly we heard a plane, so we hurried back to the shore and dived behind the dike, just before the plane came over very low. We were very lucky not to be attacked since, at this of the war, the warplanes were shooting at anything that moved. But that evening at the farm we all had a great feast of fresh fried fish. Even the soldiers joined us.

But that was not the only adventure. Joop, my brother, was looking out of the little window in the loft when he saw a German patrol finding their way through the minefield. He watched carefully and later suggested that he and I take that same route and make for Den Ham, already liberated by the Canadians. We would find out how things were over there.

It was a stupid thing to do, of course, but we set off anyway and managed to reach the village where our friends the van de Broeks lived. We were asked by the Canadian soldiers based there how many Germans there were on the farm, how they were armed and so on. It was a crazy stage of the war. There was no fighting going on, but we felt that something unusual was going to happen.

On our way back to the farm we suddenly heard “Halt!” A German soldier approached with his gun at the ready. We told him we'd been to see a doctor in the village to come and see our sick mother. We also gave him some chocolate and cigarettes - a luxury for him. He warned us of the minefields and let us go.

Dad was angry at us for risking our lives so recklessly. We realized that it had been a stupid thing to do. But at these last stages of the war, in such unusual circumstances, people were inclined to take risks. Everybody was just marking time - the Allies, the Germans and we Dutch.

Next morning, we heard the sound of many planes overhead. No anti-aircraft guns fired, so we figured that it had to be something special. Later that day, we heard those planes dropped food and medicines on the big cities to bring relief to the starving population.

The German platoon packed their bags and left for Amersfoort. We heard later they had been taken prisoner there. We realized the war was nearly over, at least for us.

A few days later, guarded by Allied soldiers, some of the Germans began clearing our area of the landmines. Soon we were able to walk the roads again. We waited for another week before deciding that Dad, Joop and I would borrow some bikes and head back to Arnhem. Mum and Bep would stay behind. The plan was for us to go and check out the state of our own house, make it livable again, and then return to the farm to collect the others.

We arrived in our hometown, only to find most of the inner-city in ruins. But our street and surroundings were still there, although badly battered, with all the windows broken, grass growing in between the street-bricks, most of the furniture broken, and with everything incredibly dirty. But we also found was that the surrogate wall Dad had built downstairs, hadn't been touched. All the linen and blankets that Mum had put behind it was still there and untouched.

We boarded up the windows, cleaned up, and after a few days cycled back to the farm. We returned home as a family.

Some time later, we heard that the Jewish family Bohemen had survived the war, too. Towards the end of the occupation, they had been caught by the Nazis and taken to Westerbork from where they were to be transported to Auschwitz. But at the last minute they were liberated by the Canadians. At least our efforts had led to a good end.

A few months passed by. Life slowly got back to normal. Then one day a car stopped in front of our door. Out of it came the Bohemen family, all dressed up nicely. The father a clothing manufacturer I think. After telling us their story, I believe that my father was given an old watch. They thanked us for what we had done for them.

But I can still see Mum looking at their clothes. They must have known how desperate we were for clothing and shoes, she'd say. My Dad also received a certificate from the Israeli delegation in The Hague in recognition of his work for the Jewish community in Holland.

We were told that a pine forest was going to be planted in Israel. Each tree would bear the name of a person or persons who had helped save a Jew or Jewish family. Well, we thought, at least Mum Dad would get some recognition.

Years later, when I had been living for a long time in New Zealand, my brother Joop made a trip to Israel, to visit his daughter who now lived there. On an impulse he made inquiries where to find this pine forest, but got no satisfaction. He tried at the Dutch Embassy there, but they couldn't tell him anything either. I wonder whether it had ever been planted?

The war in the Far East was still raging, and soon our government was asking for war-volunteers. It was still in the days of nationalism and national pride. Those volunteers would first get military training in England, because Holland wasn't ready by a long shot to train them itself.

You can guess, I suppose, that Joop and myself were among the first ones to volunteer. By the end of November, we were both in England, doing the initial course. I was selected for the Royal Engineer Corps, and Joop for the Infantry. We were both there for a whole year.

I graduated as a sergeant, and Joop was chosen for the Officers Course run in Holland by that time. I arrived back in Holland too in February of 1947, but then left for the Dutch East Indies in March.

Our company was the 6th Genie Veld Company. Our job was to construct the quarters for the bulk of our Company due to arrive several months later. We sailed on a ship called the Nieuw Holland, a fairly ancient affair. We slept in hammocks. That was really rather good, because they swung with the waves, which prevented most of us from being seasick.

We disembarked at Palembang, the biggest place in South- Sumatra. We got stationed in the Benteng, an ancient fort used by the Dutch Colonial Army. They taught us the ropes, as it were, to prepare us for the strange conditions over there.

Soon after our Company arrived we went into action. It didn't take long before most of the important places were occupied, and the planters came back to carry on from where they had left off when the Japanese overran the Dutch back in 1941.

But now Indonesian guerrillas made that difficult. They sometimes put land-mines across our supply- routes, and took potshots at small units.

I vividly remember an instant where I and four men were loading our truck with timber needed for a bridge that we were building. We were ready to leave. I was seated beside the driver when we heard a bang. We dived into the ditch and fired in the direction the shot came from, but there was no more firing. After a while we climbed back into the truck and saw holes in the front and rear windows Where a bullet had passed between the driver's and my head.

We didn't see very much action in Sumatra. The main action was on the island of Java. It was there that Sukarno proclaimed Republik Indonesia. Under heavy pressure from the US and Britain our Government was forced to grant the former colony its independence.

Our old Queen Wilhelmina probably saw the writing on the wall early on. She abdicated the throne in 1948, passing it on to Juliana, who, in 1952, I think, signed the proclamation, giving Indonesia back to the Indonesians.

I returned to Holland in January, 1950. I demobilized, in March of that year. Although I had seen much of the world, I have always regarded my Army-years as time wasted. Nearly 5 years of my life was used up.

But life goes on.

I couldn't get a decent job. Holland was now even poorer after losing Indonesia. After a year of just drifting, I decided to emigrate.

I had been in contact with one of my ex-colleagues from Indonesia. He had emigrated to New Zealand directly from Indonesia. He was working on a farm and had found a sponsor for me, making it so much easier for me.

I visited the N.Z. office in The Hague and was on my way in no time. I sailed on the Groote Beer, a Liberty ship converted to a passenger liner. It was the first ship to go to Australia and New-Zealand (from Holland). It left Rotterdam on the 17th of August 1951.

On board I soon made friends with a Dutch couple who had recently married, Arie and Jannie van Nugteren. I would see quite a bit of them later on. We arrived in Wellington on the 23rd of September 1951 where I was interviewed by a journalist of some newspaper.

We all received an 'alien book'. It contained our names and forwarding addresses. We were instructed to always contact the local police whenever our address changed. I didn't like this rule; it gave you a feeling of being kept under constant surveillance. However these were the rules in those early days, and we had to follow them.

My friend from Indonesia was there to greet me, and that same afternoon we were on our way to the King Country, to Taumarunui. The actual farm I was going to was 25 kilometres from town. It was in the middle of nowhere, at least that‘s what I thought. But the farmer's family was kind, and slowly I got used to herding sheep on horseback, digging fencepost holes, milking the cow and doing my own washing.

The meals were eaten with the family. I had my own batch, close to the house. All went reasonably well until one day, when the boss asked me to kill a sheep. I refused, because I had never killed any animal. The boss said, "You city boys are all the same. You‘ll never make a farmer.” To which I replied, “I don‘t want to be one anyway.”

I lasted for a year on that farm, but I decided not to make farming my career. I wondered what to do next. I traveled up North and headed for Tirau in the Waikato, where I knew Arie and Jannie were living. He worked as a baker in the one large bakery there. They made me most welcome, and I soon found a job in the dairy factory along with lodgings.

A few months later, Arie saw an ad in the paper. There happened to be a small bakery for sale in Kaitangata, a mining town right down the South Island. It took his fancy, and he went down there to see for himself. He came back four days later and told his wife that he had bought the place. They would start work in a few weeks' time.

Arie asked me to go with them. There was to be a room for me to rent, and plenty of work in the coal mine. That seemed a good idea, and that's how I became a trucker in the underground mine. I boarded with the Nugterens.

Then my sister Bep came out from Holland. She arrived in August, 1953 and came down to Kaitangata to stay with me. She got a job in Balclutha hospital.

But after a few months we decided to go back to Wellington, where there was plenty of work on the waterfront, and where there were also better work opportunities for Bep.

We found a nice flat in Benares street in the suburb of Khandallah. My job on the wharf suited me fine for the meantime, and there were many Dutch immigrants working there. Soon we had made a large circle of friends.

One of them, was called Gerrit Kerkmeester. His eye fell on Bep. After a short courtship they got married. He moved in with us, but it wasn't long before they bought a property in Johnsonville on, what was at that time, the main road (Middleton).

His brother Jan and I rented rooms at their place. Bep became pregnant, and when the time came, she went to Alexandra Hospital to give birth.

Just at that time Rie Ottema came out from Holland. I remember the day that I met her. I had gone to the hospital to visit Bep who had had her first baby. Bep told me that she was being nursed by a Dutch nurse who had come out from Holland very recently. I was sitting by her bed, and there came the nurse with a cuppa for Bep. And that is how I first set eyes on my future wife.